Free Meals and Logings.

Imagin a house in which you can eat the walls to your hearts content.

Insect galls are the highly distinctive plant structures formed by some herbivorous insects as their own microhabitats. They are formed from plant tissue which is controlled by the insect. Galls act as both the habitat and food source for the maker of the gall. The interior of a gall can contain edible nutritious starch and other tissues. Some galls act as “physiologic sinks”, concentrating resources in the gall from the surrounding plant parts. Galls may also provide the insect with physical protection from predators.

Insect galls are usually induced by chemicals injected by the larvae of the insects into the plants and possibly mechanical damage. After the galls are formed, the larvae develop inside until fully grown, when they leave. To form galls, the insects must take advantage of the time when plant cell division occurs quickly: the growing season, usually spring in temperate climates

Gall makers can be considered microhabitat engineers, because their galls provide both a food resource and a habitat that can be exploited by herbivorous and omnivorous organisms that do not feed on the galling insect. In part from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Let me give you an example of a Gall and the amazing web of life that surrounds it.

Goldenrod Gall. You may have observed a wooden ball sticking out of the snow during your winter hikes, you came across a Goldenrod gall. It can be a fun project to gather a few and take them home and placed into a jar just to see what emerges.

This particular specimen was created on a Showy Goldenrod. This is a common plant of the Lower Foothills, much loved by bees and butterflies.

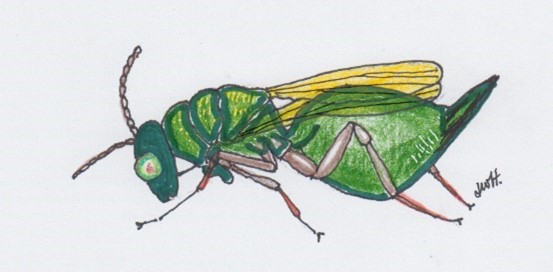

The goldenrod gall fly (Eurosta solidaginis)

With your spring walks alongside the creek, you may observed the fresh green galls. Th Goldenrod Gall flies Eurosta solidaginis are responsible for these galls. The female fly lays her eggs on the stem and on hatching the larva burrows into the plant, eating the stem’s tissue. The result from the fly larva’s appetite is a lot of excrement which has the effect of the plant sealing off the intruder by forming a gall.

Take a close look at the old gall formed later in the season. It is very woody and hard, enabling is to survive the harsh winter months. Yet they is a problem, how can an new adult fly eat its way out of its woody cell? The answer is that the larvae eats its way to the outer wall before changing into a fly. Leaving just a thin soft layer as an exit. When ready it will inflate an air bubble on its head pushing its way out to freedom.

Life within the gall is not all a haven, for a parasitoid wasp, Eurytoma gigantea can drill a hole through the gall and lay an egg in the cell, which on hatching will eat the fly larvae slowly over many weeks.

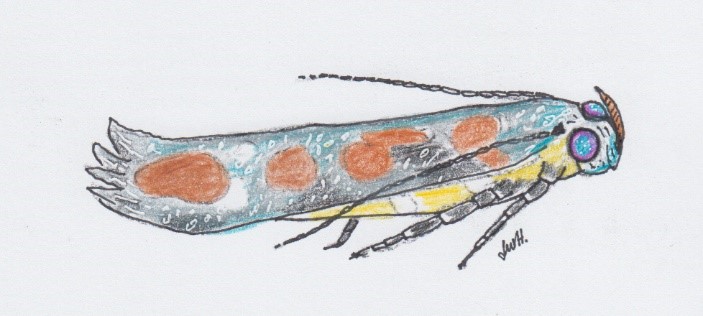

A second elongated gall can be found on these plants formed by the larvae of a tiny moth with a long name, Gnorimoschema gallaesolidaginis, or surprisingly the Goldenrod Gall Moth. This moth lays its eggs in the autumn and having overwintered, the larva enters the plant in the spring. Once full, this larva will do exactly as the Gall fly did, tunnel out to the surface then seal the exit in this case, with silk and sawdust. This exit hole is wider on its outer rim than at the inner, so the plug is shaped rather like a sink plug this makes it easy for the newly emerged Goldenrod Gall Moth to push out but hard for a potential predator to break in.

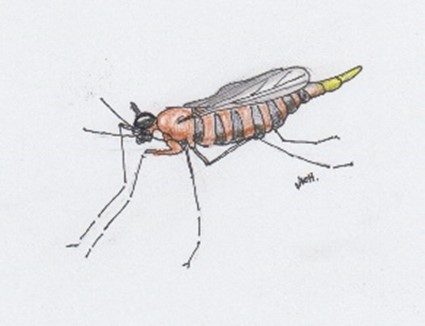

A third ‘rosette gall’ is formed from a cluster of deformed leaves, the culprit is in this case the Goldenrod Gall Midge Rhopalomyia solidaginis. None of these insects destroy the plants, only impacting them slightly

None of these Gall forming life form are really that safe. The Downy Woodpecker is an expert at drilling a hole through the galls and extracting its occupants.

Finally, The bees and butterflies visiting the flowers are not safe either. Preying on this constant coming and going of pollinators is the laziest spider I know, the Goldenrod Crab–Spider Misumena vatia. It will sit among blossoms with its front pair of legs outstretched waiting for a food item to walk into its embrace. This species comes in two color forms, one yellow and the other white; and they can change color from one to the other.

I think you will agree that what at first you may observe is only the tip of the iceberg! It can be very enlighten to follow up with some personal research at the same time be a great joy doing so.