The Alpine in Winter.

Part 3. The Alpine Regions in Winter.

It’s winter, a deep cold winter, more so in the Alpine regions, which may last for some seven months. Alas, winter is the one time of the year we can’t enter the high altitudes of the Rocky Mountains and its canyons owing to the great depth of snow there.

For this reason, we need to study Alpine’s three Sub-regions from my ‘Lazy-boy’ armchair. So please, draw up a chair and we will visit the Rocky Mountains in winter together via the internet, various books, from the sky, and our observations made during the warmer months of the year. It is cold outside! By the way, the three regions that we are considering in this post are the high Alpine, Subalpine, and Montane.

From afar, the Rocky Mountains are extremely beautiful dressed up in the snow at this time of the year and it is a great joy to take pictures of them, from a distance.

Altitudinal Migrators.

The long winters that cover the alpine regions, beg the question, how does life survive up there? The answer for most of the large mammals is that they migrate down to the Montane or the Foothills.

The cold wind and blowing snow off the high-country offer challenges greater than most animals can adequately cope with. For animals that remain active during winter, these lower elevations offer easier access to food and more protection from the elements. Animals that move from areas of higher elevations to the Montane are considered “altitudinal migrators”. Elk, Moose, and White-tailed deer are three examples of animals that move in this way. The exceptions are the Grizzly and black bears, which hibernate in ice caves under the snow. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Altitudinal_migration

As mentioned earlier the Elk, Moose, and Deer will come down to the Foothills during the winter months. When the snow gets deep, these deer will yard up (stay in one location) since bounding through snow requires a lot of energy. The Mule and White-tailed Deer have such small feet about their size, that they sink through the snow. By yarding, they create a network of trails that allows them to reach areas containing winter food. At the same time, there are risks associated with it. During long, hard is especially admirably adapted for it with their long legs. However, moose will frequently follow already established trails, while elk tend to follow trails made by their strong lead animal. These modes of travel are known as trailing, and they are a means of reducing energy output. I too often use these ‘game trails’.

Grizzly Marmot.

Grizzly Marmots, like many other members of the squirrel family, hibernate through the winter months. They survive on the fat they have stored throughout the winter and conserve energy by slowing their metabolism. Hibernation varies by species, but some marmots will hibernate for up to nine months. Marmot – Description, Habitat, Image, Diet, and Interesting Facts (animals.net)

Hibernation.

Whether animals, like bears and chipmunks, hibernate, is open to question for living things do not follow definitive rules. Thus, there is a continuum between the “true hibernation” of ground squirrels and marmots in which all bodily functions are greatly slowed and the light sleep of bears and chipmunks, and the occasional sleep of raccoons and squirrels where hibernation is intermittent. Bears are said to not truly hibernate because, although their bodily processes are slowed, they do not have the reduced body temperatures of other “true hibernators.” But bears develop thick coats of fur and have less surface mass ratios than smaller hibernators, so they stay warmer. Bears’ metabolism drops by half and their digestive system tightens into a knot, with the limited waste products reprocessed into the bloodstream in the form of proteins. Bears, if not true hibernators, are certainly close. Bears sleep for months without eating, drinking, urinating, or defecating.

America Pika.

Despite the deep snow, there is life up there, high in the alpine. For one, I love the American Pika (Ochotona princeps) which will remain active all winter within its den hidden among rockslides and boulders and deeply covered with snow. It will feed on its “haystack” which is made up of grass that was cut, dried, and stored during the summer months. It is admirably adapted to survive the long and extreme winter conditions. It has small round ears, an inconspicuous tail, and short legs which reduce surface exposure and heat loss; also, the fur insulates the soles of its feet and provides good traction. Pikas may look like rodents, but they are related to rabbits.

This tiny ‘rabbit’ is active during daylight hours and does not hibernate. Pikas deposit two kinds of fecal droppings: Hard, brown, round pellets and pellets that are soft black shiny strings that form in the caecum. Caecal pellets have more energy value than stored plant food and the pika may consume them directly or store them for later. Pattie and Fisher, Mammals of Alberta. Lone Pine 1999.

Ptarmigan.

The Ptarmigan is the only bird that remains at or above the treeline throughout the winter. This alpine cousin to the grouse changes its brown plumage to white as autumn light diminishes and winter snow begins to blanket the mountains. Its feathered feet function as snowshoes, just like the Pika, which allow it to walk on snow. Sharp claws help it scratch for food beneath the snow as Ptarmigan will feed on willow buds and the needles of subalpine fir. Warmth and protection from winds and sub-zero temperatures are attained by diving head-first into the snow and becoming completely buried.

Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep.

Mountain goats are the largest mammals remaining active in the high country year-round. Their heavy wool undercoats and long hollow guard hairs protect them from the cold and wind. Mountain goats can subsist on lichens and mosses if they cannot find adequate browse. In winter goats move to lower latitudes where the prevailing winds blow the snow away, exposing the lichens and vegetation.

Photo by Judy Taylor.

Snowshoe Hare.

Snowshoe hare Lepus americanus, and weasels, like the Ptarmigan, also turn white. This is due to the absence of the pigment melanin in their fur which creates more air spaces within the hairs and thus it has greater insulation value. Photoperiod triggers hormonal changes that are also influenced by cold and snow. As its common name “snowshoe” suggests it is the large size of its hind feet which prevent it from sinking while traveling across the snow. Its feet also have fur on the soles which help distribute their weight and protect them from freezing temperatures. Surprisingly, the Snowshoe hare does not hibernate up here and it is mainly active at night. During the day it will find a sheltered spot and rest in a self-made depression called a ‘form’. The female snowshoe hare may have up to four litters in a year, which average three to eight young. Males compete for females, and females may breed with several males therefore they can reach high population numbers may be reaching some 500 to 600 per square kilometer. Air temperatures and wind can also alter snow crystals over time to form a hard, compacted snow mass with an even temperature throughout. This type of snow is difficult for mice to burrow through. Yet, this same snow allows snowshoe hares and deer to reach up higher in shrubs and trees in search of food.

Photo by Gordon E. Roberston

Short-tailed Weasel.

Another beautiful predator is the Short-tailed Weasel Mustela erminea, with a black-tipped tail and a long, slender body that can easily squeeze down the narrow burrow. It boldly enters a mouse’s tunnels to kill and eat its occupants and it will sometimes build a nest of mouse fur and use the tunnel system for its own. Weasels also undergo a complete molt. Each hair is lost, and a new white hair replaces it.

After mating the female weasel can undergo embryonic diapause, meaning that the embryo does not immediately implant in the uterus after fertilization, but rather lies dormant for a period of nine to ten months. The gestation period is therefore variable but typically around 300 days, and after mating in the summer, the offspring will not be born until the following spring – female weasels spend almost all their lives either pregnant or in heat. Females can reabsorb embryos and in the event of a severe winter, they may reabsorb their entire litter.

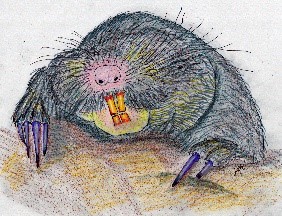

Northern Pocket Gopher.

Another winter-active creature is the Northern Pocket Gopher. Even with the ground covered with snow, pocket gophers will bring up spoil to the surface and pack it into the snow. When the snow melts these soil cores are left exposed. This is because pocket gophers commonly backfill their previously excavated tunnels with excess soil as they dig new tunnels These long, branching tubes of soil result on the surface. This is what we will see in the spring when the snow melts.

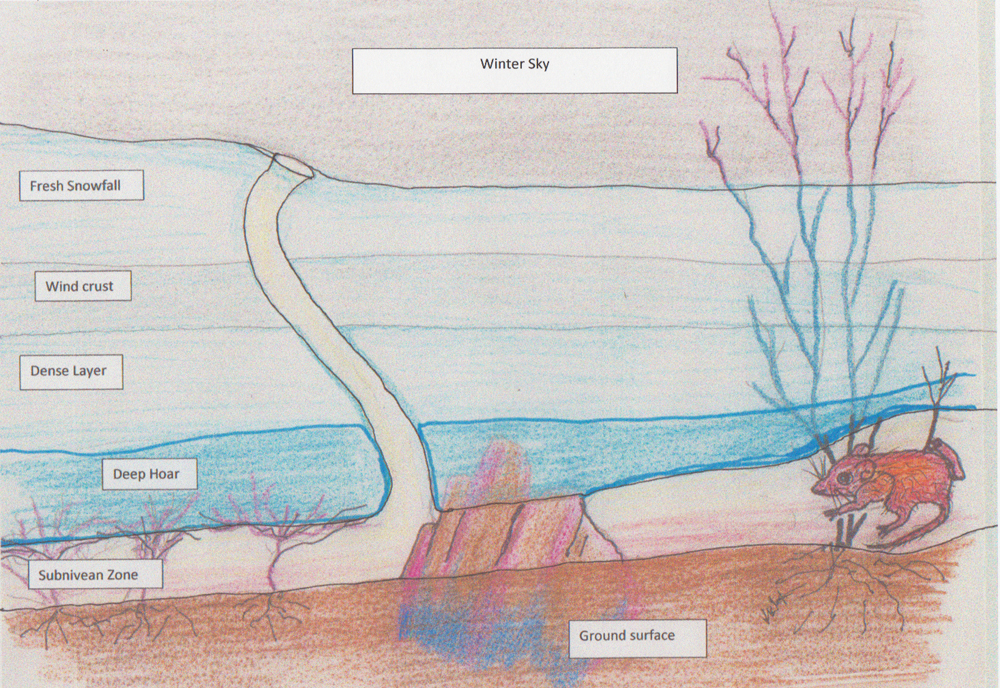

Life Under the Snow.

As with the alpine, little life can be seen at this time of the year, yet it is there. The snowpack itself is the reason for their survival. This snowpack is laid down into layers, with living space at its base termed the subnivean zone. Here, life can survive over the long winter months. This space is created by the rocks and vegetation holding up the snow, and leaving a living, breathing space for life to thrive.

The substrate at the base of the snow is slightly warmer than the snow’s surface forming a roof and a living space below it. Voles, shrews, mice, insects, and spiders can be active all year round with a possible temperature of -2°C.

Many animals live in and depend on the subnivean zone for winter survival. The most frequent are small mammals including mice and voles. These animals spend most of their winter eating plants ,seeds ,and bark from bushes and shrubs. Both mice and voles will often store amounts of food to ensure a steady supply. While these animals are active throughout the winter, they do spend small amounts of time huddled together in a deep sleep, waking occasionally to feed.

These small rodents and their series of tunnels will lead from entrances to sleeping areas and their sources of food. The entrance holes up to the surface double as ventilation shafts, allowing the carbon dioxide created from animal respiration, as well as carbon dioxide released from the ground, to escape. This helps to keep the concentration of the suffocating gas to non-lethal levels.

Life above the Snow.

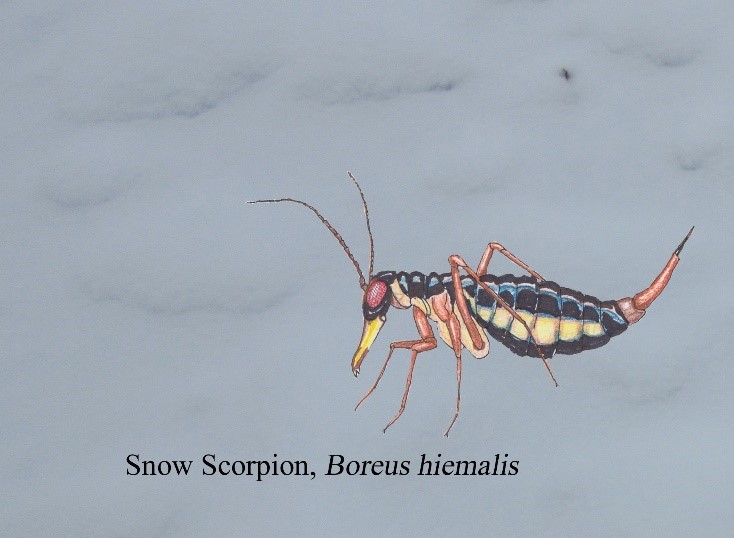

Snow Scorpion.

A few insects may be seen, dark-colored, stark against the blinding-white snow. Most frequent is the Snow Scorpionfly Boreus hyemalis they are admirably adapted to the freezing conditions if you were to hold one in your hand it would probably die from the heat. The larvae feed on the mosses under the snow When the adults appear, they will be seen walking across the snow’s surface seeking a breeding partner. This wingless insect is close relative to the fleas, yet it looks more like a six-legged spider. Like fleas, it can jump when alarmed using its middle and hind legs but unlike fleas which use their hind legs only. Snow Scorpions are an ancient group that may have given rise to the moths and butterflies, for they undergo a complete metamorphosis.

The male uses his stubs of wings to hold the female while mating and later will carry her about on his back After mating she will work her way down under the snow to lay her eggs on some moss.

Snow Fleas.

Whilst snowshoeing through the spruce trees of the Upper Foothills I came across a patch of black specks on the surface of the snow, and they moved. Yet I have met them before, Snow fleas, possibly Hypogastrura toolkit. They are not fleas but Collembola or springtails. Despite the cold, these tiny insects of the forest were quite lively. Most springtails have a special ‘lever’ under their body called a ‘furcula’ which can catapult them high in the air, hence their common name. I have since read that they produce their anti-freeze, a protein containing glycine. They spend most of the time under the snow being part of the soil’s ecosystem eating detritus, fungus, and decaying plant material thereby part of the detritus cycling. www.Biodiversity150; visited October 2021.

You may like to visit, Part 3a Alpine Plants in winter