SPIDERS, Part 5. Sexual Selection in Spiders.

Recall, from Part 3. That the male will take a considerable risk when going a courting.

Darwin, in his book Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favored Races in the Struggle for Life, suggested that Sexual Selection plays an important part in developing life forms.

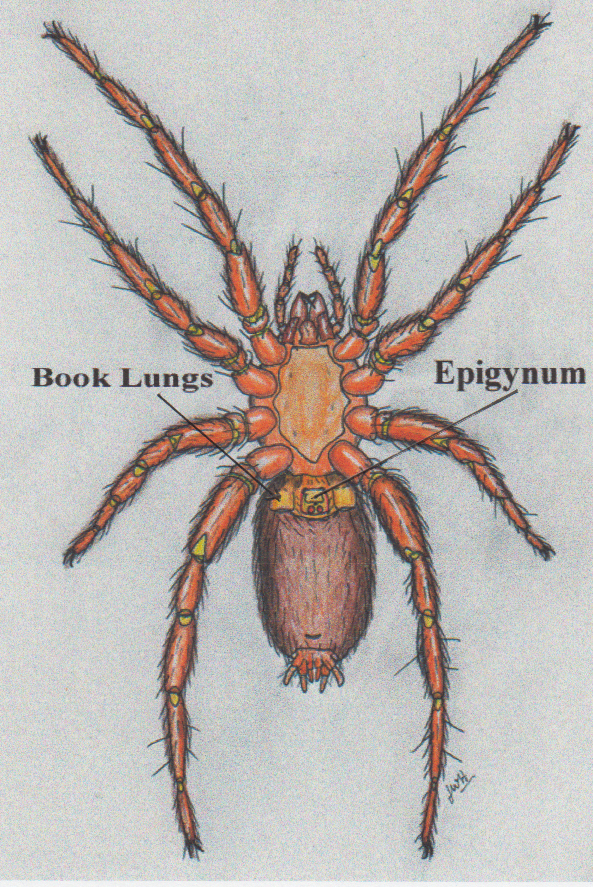

A Female Cat Spider

Having spent a fair quantity of time studying the cultivation of tarantulas and true spiders. I have concluded that sexual selection plays a significant part in a species’ natural selection, at least in spiders.

We will provide an example with the Cat Spider, which you may be familiar with, as this spider often builds its orb web across a lit window. In this way, she receives a supply of moths every evening. She will be pretty significant, her abdomen full of eggs.

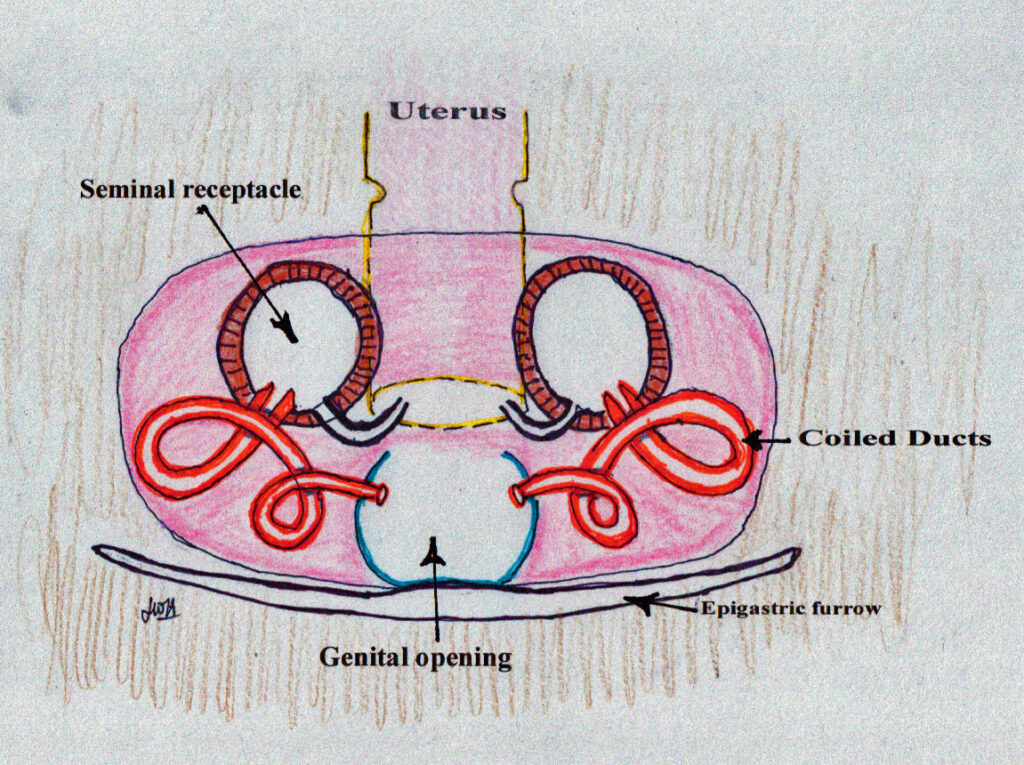

As you may know, the female epigynum plate lies between the anterior book lungs. This epigynum is not visible unless one examines the cast skin of a mature female spider. Better still would be a dissection, along with the removal of the tissue surrounding the organ. Hence, these illustrations are a quick way to make my point. An illustration is worth a thousand words. This Drawing is (After Wichle, 1967).

Yet the female “often as not” makes mating with a male exceedingly difficult. The path between the female sex aperture and the spermatheca, where the sperm is stored, consists of a tube which the female has evolved into a series of long, convoluted bends, making it an arduous journey to take. Only the fittest of males with an embolus are adapted to achieve this manoeuvre—diagram after Melchers, 1963.

The male sexual apparatus has to keep up with the female’s deliberate obstructions, thereby creating a “lock and key” system. During mating, the male’s embolus is inserted through the external genital opening and then on into the sperm duct. Both structures must match.

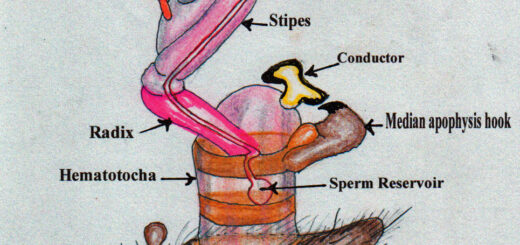

The male’s reproductive organs have also developed into a complex system of interlocking parts in his efforts to deliver his gametes. Recall from part 2 that this complex organ metamorphosed from a simple palp.

The male’s reproductive organs have also developed into a complex system of interlocking parts in his efforts to deliver his gametes. To navigate the twisting bends leading to the female’s spermatheca. He needs an anchor point and be able to twist and turn the embolus to achieve the delivery. This drawing is based on Grasshoff (1968).

The male’s adaptations to his papal apparatus have become very complex.

The courting procedure for females is challenging enough, yet the male has a complete toolkit, enabling him to pass on his genes to the next generation. First, the hook of the median apophysis engages with the tip of the female’s scapus. The scapus, by the way, is a tube used for egg-laying; it also covers her sexual opening. The hook then turns to secure a tight hold on the scapus, the turning being driven by the inflation of the soft hematodochae hydraulically. This expansion of the hematodochae provides the energy to shift the positions of the radix and stipes, bringing the embolus into position. This inflation also causes a rotation of the tegulum, which in turn presses the conductor to one side of the scapus and the embolus into the epigynum. This drawing is based on Grasshoff (1973).

Conclusion.

The Female spider improves her reproduction success by selecting the most promising male. The male, on the other hand, needs to keep up with her demands.

As an end-note, recall that the male elaborates the copulatory organ – the palp. A rose from the simple structure shown here, which consists of just two internal muscles and one claw.

Enjoy, and keep reading.

JohnH.